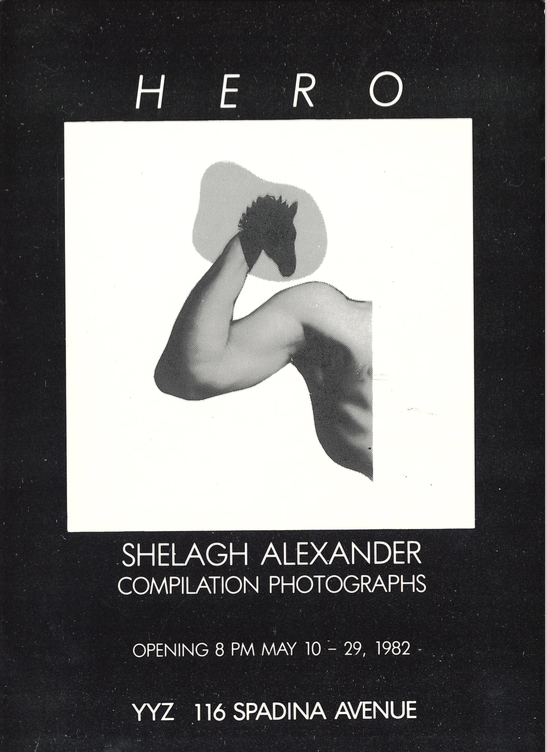

Shelagh Alexander (1982)

“Shelagh Alexander: Hero,” Parachute, no. 28 (September – November 1982), p. 42.

Or scroll below.

SHELAGH ALEXANDER

YYZ, Toronto May 10 — 29

A single photograph indexes the present within the formal limits of its frame. It presents that (formal) moment as a static, wordless mirror, heedless of duration or decay, of affect or statement. Sometimes that presence is diverted or delayed by language, as in a caption beneath a newspaper photograph, for instance, but words hardly ever encroach upon the image except in the slick images of advertising or its exact counterpart, semiotic critique. And if the photograph lends itself to narrative, it is through the moving image of film, or sequentially as the pages of a photo-book, never as a still image.

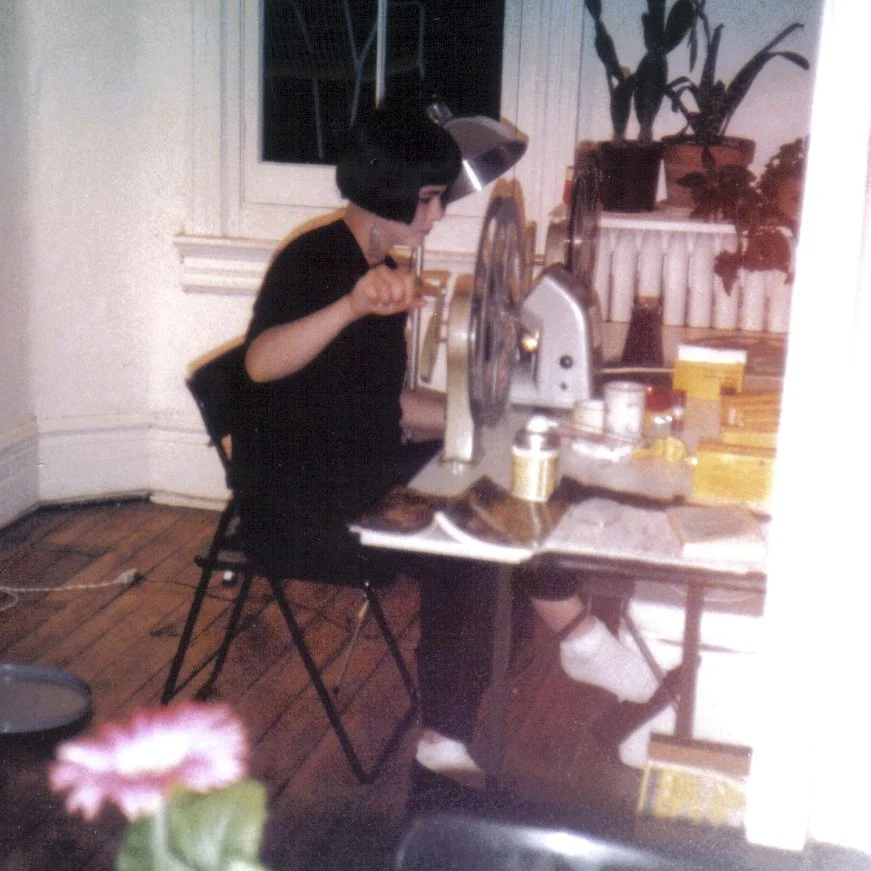

In the first part of Shelagh Alexander’s Hero, a narrative, or more properly, a fable, is the means to move the viewer through the compilation and conflagration of imagery. Alexander calls this three part series of fourteen 30” x 40” panels “compilation photographs.” In this process, selected images from different negatives are systematically printed on the photographic paper through a registration system that uses as many as twenty rubilith stencils per print. Text and drawing are treated to the same photographic production. Making their own space, and giving each of the three parts its own character, the images overlap, passing from panel to panel and composing horizontal sequences in the first two parts and a vertical progression in the third.

The impression of visual jumble in Part One is dispersed by the narrative which cues action to general figures of photographic reference and by an overall figurative composition—the drawn outline of the head of the “Beast.” This part opens in an urban hell, specific to the viewer’s own urban context, but apocalyptic. “Caught in the head-lights of a swiftly approaching car,” the female protagonist is also destined for the mouth of the Beast as it is coincident with the triangular beam thrown by the headlights of the car. The mouth of the Beast is that consuming city: into the tenement and apartment-toothed mouth of the Beast, flaming bodies, crashing airplanes, crazed horses and burning dogs tumble.

From a common reality that has already been made figurative, in Part Two we are transported to a fabulous realm signalled by the “exotic” desert and classical ruins—a mélange of primitive religion and Dionysiac madness (spiral-dazed eyes of rearing horses) and Disney-land castles “built on the back of misery and death.” Having seen the Beast for the first time and out of disgust for all those affected by it, she raises a kingdom “from the dust of destruction, built by those infected by the beast and kept in darkness beneath a palace.” And so the horizontal orders these panels—the palace above the workers, and pyramids above a tunnel—with subterranean madness and slavery signifying the seeds of a class war.

By the end of this part, the series has become a narrative of the quest for individual wisdom, based on the allegory of the archetypal hero’s quest and trial, as the “King,” her father, casts his daughter into the “deepest hole” to learn wisdom for her human abuses. Here, in the ascending final panels, the princess is instructed by the Beast: “The mirror is the key, look into it and you will discover that it is merely a shallow grave. Look beyond it, and you will find a broad road which shall carry you far further than you have ever gone before.” She discovers that road that sets her free as a sympathy and solidarity with the workers who built it beneath her palace.

This is not the happy end and simple narrative wish-fulfillment, for the headlights she discovers on this road return her to those in Part One. Part One now functions as the fourth part of the series, changing the interpretation of that narrative and offering a bifurcated ethical choice. This return is a hinge: having seen the Beast for the first time she chooses either its ways as the narrative at first implied in building her palace on the back of misery and death or she combats it (“I refuse to turn away again”). This complex return and bifurcation “saves” this fable from its naivety. The work operates as a multilevel narrative space with its context and temporal shifts from the commonplace to the fantastic/heroic and back again, returning the allegorical to action in everyday life: the circular structure returns us to the urban reality we know. The work can be divided into story and discourse levels in terms of both its narrative and photographic construction. The story level is of the order of the fable and of the found or taken “to order” photographs which do not illustrate the text as much as create a ground for its interpretation. The discourse level is the structure of the narrative and the unique creation of photographic space specific to the techniques of compilation. Finally, the content finds its photographic expression which is a critique at the same time. The shallow grave of the mirror is formal photography; the road, photography’s narrative path. What at first appeared a charming tale, in the risk of naivety, ends in being a complex expression and courageous statement.